“I never thought I’d see this in my lifetime. I haven’t seen the wolves yet but they are about for sure. My neighbour saw four just a month ago slipping into the woods along the brow of the hill. ” said Jack Lewis, resident of Devauden, Monmouthshire for fifty-five years.

The realisation of wolf reintroduction in the South Wales-England borders region is the culmination of a long process of research and development supported by public opinion and political change. In particular this process was accelerated by the radical changes in thinking and policy which followed the visionary Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act of 2015 and subsequent declaration of a Climate Change and Ecological Emergency in 2019 by the Welsh Assembly and UK government. The cataclysmic impact of the Covid-19 virus in 2020 and corresponding economic recession was the systematic shock which profoundly shifted everything. The social activism, pressure and scrutiny of social movements such as Extinction Rebellion supported the unprecedented and rapid shift of policy declarations into decisive action.

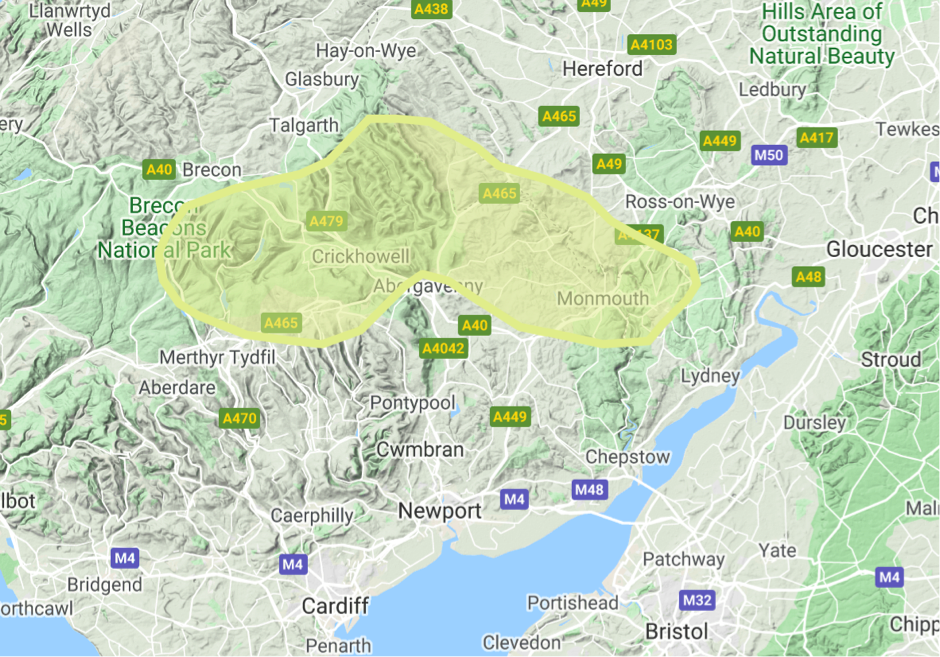

The borders reintroduction programme was developed and overseen by a consortium of cross border and cross sector organisations. Following a long and concerted period of habitat restoration and connectivity, the region was eventually considered bio-secure for wolf reintroduction. The pioneering Lakeland pack reintroduction in Cumbria was the stimulus needed to activate the programme. Rather than wait for the Cumbrian pack to naturally grow and geographically disperse, which is still practically difficult due to the lack of habitat connections across the UK, five wolves were relocated from Romania to Wales in order to add to the UK wolf gene pool.

Wolves highlight the absolute importance of habitat connectivity, a simple reality which had been undervalued and disregarded through decades of infrastructure and building development in the UK.

According to chief ecologist consultant on the programme Megan Fowler:

“This reintroduction programme very much follows on from the success of past predator and keystone species translocations- such as the Pine Martin and Eurasian beaver in the Wye Valley and of course the famous Lakeland wolf pack in Cumbria. Pine martins are playing a critical role in Wye valley woodlands as a biocontrol of grey squirrel populations and opening up the potential for red squirrel recovery. The Eurasian beaver is helping to establish rich wetland habitats that support greater numbers of invertebrates, amphibians, fish and birds. We are hopeful the wolves will have a similar impact on deer and boar numbers in the locality. Both of these populations are causing extensive damage to Forestry and costs of managing them are significant.”

Reflecting on the process so far Megan Fowler outlined,

“We worked closely with Suzanne Hargreaves, head of the Lakeland re-introduction and her team to learn from their modelling process and monitoring data. The modelling of wolf pack dispersal establishment that we carried out during the initial feasibility study was very accurate and we now see the potential for dispersal of this pack to the north Wales area, eventually linking up with the Lakeland pack. Roads continue to be a big risk to the viability and expansion of the wolf population and we are investing hugely in connectivity measures, such as large scale overpass and underpass structures”.

Vital to the success of this reintroduction has been the step change in the way land is owned and managed and the wholesale reconfiguration of agricultural and farming methods. This has meant that historic conflicts such as that between an upland sheep farming and large predators such as wolves is now much diminished.

According to Peter Howells, regeneration officer for the Welsh Assembly,

“The long process of land asset transfer and establishment of community land stewardship and new community enterprises started in the South Wales valleys by projects such Skyline has transformed our approach to rural development and notions of value”

Rhiannon Williams, community outreach coordinator with Aethnenni woodland community interest company based in Monmouth adds,

“While there is still a certain level of fear of wolves and opposition to their reintroduction, we have to accept that this is a huge cultural transition for people. Negative connotations of wolves run deep in our psyche having developed over hundreds of years. Fortunately, due to the adaptability of humans, the presence of wolves is quickly normalising. In fact, actual experience is showing that the wolves are working with us not against us…. supporting our community enterprise to sustainably manage the woodlands by keeping down deer numbers and allowing trees to establish and mature. We are moving beyond a mindset of nature as something which exists in nature reserves and on nature programmes to an awareness and acceptance that we live within nature.”

The Wye Valley and Welsh borders wolf pack is now considered stable and with the addition of two pups this year now numbers twelve. The pack often breaks into smaller groups on hunting expeditions and recent observations are signalling that the UK may have it’s first lone wolf or what is sometimes referred to as ‘casanova’ wolf. Radio tag data and observations show ‘Seren’ a yearling wolf to be spending increasing amounts of time alone away from the pack. This reflects a process known as dispersal whereby individual wolves leave their family to look for a pack of their own to prevent inbreeding. Very few wolves remain lone wolves. So far it is not clear whether Seren was excluded or left independently but she is in a precarious position.

While the pack is stable, it is still isolated from the UK’s only other wolf pack. While our native predators are successfully acclimatising, the UK’s wolf population is not as yet genetically resilient.